KEDA: Event-Driven Autoscaling for Kubernetes

Introduction: Why KEDA Is Relevant Today

In recent years, Kubernetes has standardized autoscaling through the Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA), mainly based on CPU and memory metrics. This approach works well for synchronous, CPU-bound workloads, but it shows clear limitations in event-driven architectures — such as queue consumers, stream processors, asynchronous jobs, and integrations with external systems.

In these scenarios, the true signal of load is not CPU utilization, but the work backlog: queued messages, Kafka lag, pending events, and application metrics. This is where KEDA comes into play: a Kubernetes-native component that enables autoscaling driven by real events, including scale-to-zero — something impossible with pure HPA.

This article is designed for DevOps engineers, Platform Engineers, and SREs who want to deeply understand KEDA and implement it correctly in production, avoiding common mistakes and understanding architectural trade-offs.

What KEDA Is — and What It Is Not

KEDA (Kubernetes Event-Driven Autoscaling) is a Kubernetes operator that extends HPA by providing external metrics derived from event systems.

It is important to clarify a few points immediately:

- KEDA does not replace HPA → it extends it.

- KEDA does not execute workload → it decides when and how much to scale.

- KEDA is not an event source → it observes existing event sources.

The key value of KEDA is its ability to:

- scale from 0 to N pods,

- base scaling on real event sources (RabbitMQ, Kafka, Prometheus, cron, etc.),

- integrate natively with the Kubernetes API.

KEDA and GenAI Workloads: Why It Matters for LLMs on Kubernetes

KEDA’s value becomes even more evident when observing next-generation workloads, particularly those related to Generative AI and Large Language Models (LLMs).

As recent literature on deploying GenAI systems on Kubernetes highlights, these workloads often exhibit highly irregular patterns: long periods of inactivity followed by sudden bursts of high-compute inference requests.

In such scenarios, traditional metrics like CPU or memory do not represent real workload in a timely or reliable way.

For LLM services, the true signal of pressure is not resource utilization after the fact, but incoming demand — inference requests, asynchronous job queues, pipelines orchestrating retrieval, embedding, and generation.

Scaling only when CPUs or GPUs are already saturated means reacting too late, with direct impacts on latency and cost.

KEDA enables a different approach: it allows scaling of components in a GenAI architecture based on the events that generate work, not on the consumption of resources that execute it. This makes it possible to:

- anticipate load spikes,

- reduce over-provisioning of expensive resources (such as GPUs),

- scale inference services to zero when they are not used.

In this sense, KEDA is not just an autoscaler for event-driven microservices, but an architectural enabler for efficient execution of LLMs on Kubernetes, especially when combined with HPA and cluster autoscaling.

This same principle — scaling on real demand rather than resource utilization — underlies KEDA’s architecture and its integration with HPA.

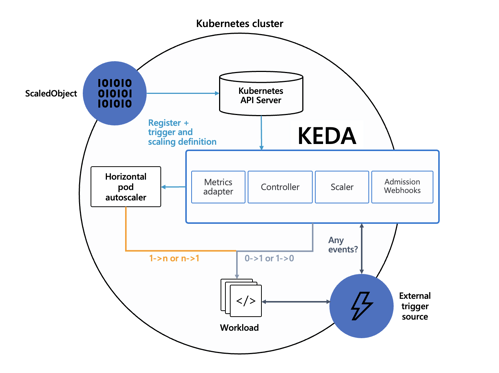

Architecture of KEDA (How It Really Works)

KEDA’s architecture is intentionally simple and aligned with Kubernetes patterns.

Main Components

- Scaler

- Each scaler is responsible for a specific event source.

- Examples include RabbitMQ, Kafka, Azure Service Bus, Prometheus, and Cron.

- It retrieves a semantic metric (for example, queue length or consumer lag).

- Controller

- Watches the Custom Resources (ScaledObject, ScaledJob).

- Decides when to enable or disable scaling.

- Metrics Adapter

- Exposes metrics through the External Metrics API.

- Allows the HPA to consume them as if they were native Kubernetes metrics.

- Admission Webhook

- Validates configurations (CRDs)

- Prevents structural errors at runtime.

Integration with HPA

The actual scaling flow works as follows:

- You define a ScaledObject.

- KEDA automatically creates an HPA.

- KEDA manages:

- scaling 0 → 1

- scaling 1 → 0

- HPA manages:

- scaling 1 → N

This design avoids reinventing autoscaling and preserves full compatibility with the Kubernetes ecosystem.

ScaledObject and ScaledJob: Choosing the Right Tool

ScaledObject

Use it when:

- the workload is long-running,

- it scales a Deployment or StatefulSet,

- you want consumers always ready when events arrive.

Features:

- supports scale to zero,

- dynamic replica count,

- perfect for microservices and consumers.

ScaledJob

Use it when:

- each event is an independent unit of work,

- you want real Kubernetes Jobs,

- the pod must terminate after processing.

Features:

- 1 event → 1 Job,

- ideal for batch processing, ETL, asynchronous tasks,

- automatic cleanup of completed jobs.

Key Trade-off:

ScaledJob provides perfect isolation but increases scheduling overhead.

ScaledObject is more efficient for continuous workloads.

Installing KEDA

Recommended Method: Helm

helm repo add kedacore https://kedacore.github.io/charts

helm repo update

kubectl create namespace keda

helm install keda kedacore/keda --namespace kedaWhy Helm in Production

- controlled versioning,

- easy upgrades and rollbacks,

- clean CRD management.

Alternative: YAML Manifests

Useful for quick tests or extremely controlled environments:

kubectl apply -f https://github.com/kedacore/keda/releases/download/v2.18.2/keda-2.18.2.yaml

Anatomy of a ScaledObject (Understanding It Line by Line)

Core Parameters

| FIELD | WHY IT MATTERS |

|---|---|

| scaleTargetRef | Links KEDA to the workload |

| pollingInterval | Event polling frequency |

| cooldownPeriod | Scaling stability |

| minReplicaCount | Enables scale to zero |

| maxReplicaCount | Protection against runaway scaling |

| idleReplicaCount | Number of “idle” replicas (if you don’t want to scale to zero) |

Advanced Section

This section controls fine-grained scaling behavior.

restoreToOriginalReplicaCount

true: restores the original Deployment replica countfalse: uses ScaledObject limits

horizontalPodAutoscalerConfig.behavior

- avoids aggressive oscillations,

- allows immediate scale-up and controlled scale-down.

In production, configuring behavior is strongly recommended.

Real-World Example: Autoscaling a RabbitMQ Consumer

Goal

- Java consumer running on Kubernetes

- RabbitMQ as the event source

- Automatic scaling from 0 → N → 0

Scaling Logic

KEDA calculates:

desiredReplicas = ceil(queueLength / targetValue)

Example:

- 100 messages

- target = 5

- → 20 pods

This approach:

- maximizes parallelism,

- avoids over-scaling,

- preserves operational predictability.

Why Cooldown Is Essential

Without a cooldownPeriod:

- continuous scale-up / scale-down cycles,

- instability,

- unnecessary costs.

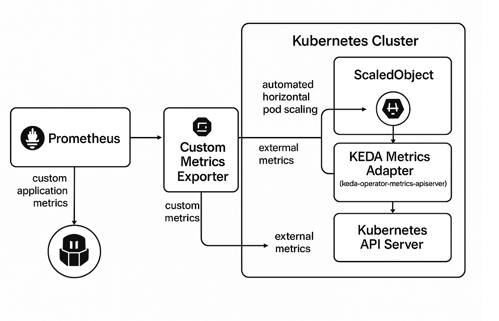

Authentication in KEDA: A Structural Concern, Not a Detail

When KEDA is introduced into a Kubernetes cluster, autoscaling is no longer a purely “internal” cluster concern.

By definition, KEDA scalers must communicate with external systems: message brokers, databases, cloud APIs, and metrics exposed outside the cluster.

This fundamentally changes the security model.

With Classic HPA:

- metrics are local (CPU, memory),

- no application credentials are involved.

With KEDA:

- each scaler must authenticate against an external system,

- those credentials become part of the scaling control plane.

Treating authentication as a configuration detail is one of the most common — and most dangerous — mistakes when running KEDA in production.

Core Principle: Separate Scaling, Workload, and Secrets

KEDA intentionally introduces an indirection layer between:

- the workload being scaled (Deployment / Job),

- the scaling logic (ScaledObject / ScaledJob),

- the credentials required to read metrics.

This principle is critical for three reasons:

- Security

- No credentials hardcoded in application YAMLs.

- Maintainability

- Rotating passwords or tokens does not require workload changes.

- Observability and Audit

- It is clear who accesses what and why.

This is where Secret, TriggerAuthentication, and authenticationRef come into play.

Authentication Flow in KEDA

Conceptually, the flow is:

- KEDA reads the ScaledObject

- Finds an

authenticationRef - Resolves it to a TriggerAuthentication

- The TriggerAuthentication:

- reads one or more Kubernetes Secrets (or an external secret)

- Credentials are used only by the scaler

- The scaled Deployment is unaware of this process

This is a crucial point: the scaled pod does not need to know the credentials used for scaling.

Recommended Pattern: Secret + TriggerAuthentication + ScaledObject

This is the reference pattern for real environments.

1. Kubernetes Secret

The Secret contains only sensitive data, no logic:

- host

- username

- password

- connection string

- token

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: rabbitmq-secret

type: Opaque

data:

host: <base64>

username: <base64>

password: <base64>The Secret lives in the application namespace, follows RBAC rules, and can be rotated without touching KEDA.

2. TriggerAuthentication

TriggerAuthentication maps Secrets to the parameters expected by the scaler.

apiVersion: keda.sh/v1alpha1

kind: TriggerAuthentication

metadata:

name: rabbitmq-trigger-auth

spec:

secretTargetRef:

- parameter: host

name: rabbitmq-secret

key: host

- parameter: username

name: rabbitmq-secret

key: username

- parameter: password

name: rabbitmq-secret

key: passwordThis is the most important part:

parameteris not arbitrary,- it must exactly match what the RabbitMQ scaler expects.

This makes authentication explicit, typed, and verifiable.

3. ScaledObject with authenticationRef

The ScaledObject simply states:

“For this trigger, use that identity”.

triggers:

- type: rabbitmq

metadata:

queueName: queue001

mode: QueueLength

value: "5"

authenticationRef:

name: rabbitmq-trigger-authThe result is a clean separation:

- ScaledObject → scaling logic

- TriggerAuthentication → identity

- Secret → sensitive data

Why Avoid Inline Authentication (Except for Demos)

KEDA also supports faster configurations, such as direct secretKeyRef inside triggers.

Useful for tests and PoCs, but with clear limitations:

- couples scaling logic and credentials,

- complicates credential rotation,

- reduces readability of the flow.

In shared or regulated environments, this approach does not scale organizationally.

ClusterTriggerAuthentication: Multi-Namespace Scaling

In enterprise environments it is common to have:

- multiple namespaces,

- multiple teams,

- a single shared broker or external service.

Standard TriggerAuthentication is namespace-scoped.

To avoid duplication, KEDA introduces ClusterTriggerAuthentication.

| OBJECT | SCOPE |

|---|---|

| TriggerAuthentication | Namespace |

| ClusterTriggerAuthentication | Cluster-wide |

Advantages:

- a single identity definition,

- reusable across multiple ScaledObjects.

The Secret itself remains in the application namespace, preserving sensitive data isolation.

External Secrets: HashiCorp Vault and Beyond

For high-compliance environments (PCI, SOC2, regulated workloads), KEDA can read secrets directly from external systems such as HashiCorp Vault.

In this scenario:

- KEDA does not read Kubernetes Secrets,

- it queries Vault using an authentication method (token, Kubernetes auth, etc.),

- it dynamically resolves scaler parameters.

The trade-off is clear:

- more security

- more operational complexity

This is an architectural choice, not a universal requirement.

Available Scalers and When to Use Them

One of KEDA’s strengths is the abstraction of the event concept.

What matters is not where the load signal comes from, but how accurately it represents real work.

For this reason, KEDA supports many scalers, each designed to translate a specific type of event or metric into a coherent scaling decision.

Queue-Based Scalers

(RabbitMQ, AWS SQS, Azure Queue)

Ideal when message backlog directly represents system load.

The number of queued messages is a clear and immediate measure of work to be processed, making these scalers perfect for asynchronous consumers and integration pipelines.

Stream-Based Scalers

(Kafka, EventHub, Pub/Sub)

Designed for high-velocity, high-throughput systems where consumer lag is the real pressure indicator.

CPU and memory are secondary metrics; accumulated stream lag drives scaling decisions.

Metric-Based Scalers

(Prometheus, Datadog)

Useful when load is expressed via aggregated application metrics such as request count, response time, or custom counters.

Effective when no explicit queue exists but work can be represented by observable metrics.

Time-Based Scalers

(Cron)

Perfect for predictable workloads or controlled operating windows.

They allow scaling based on time, such as increasing capacity during known peak hours or reducing it during scheduled idle periods.

Database Scalers

(Redis, PostgreSQL, MySQL)

Useful when application state resides in data structures or tables.

The number of records in a specific state (for example, “pending” or “queued”) becomes the signal driving scaling, keeping the system aligned with actual work.

In KEDA, scaling is not driven by CPU usage, but by the operational truth of the system:

if a signal is measurable and represents real work, it can drive scaling.

In KEDA non si scala sulla CPU, ma sulla verità operativa del sistema: se un segnale è misurabile e rappresenta lavoro reale, può guidare lo scaling.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

1. Using KEDA as a Full Replacement for HPA

KEDA is not a replacement for HPA, but an event source that extends its capabilities.

In many scenarios, especially CPU-bound or memory-bound workloads, HPA remains the most stable and predictable solution.

Best practice:

Use KEDA to translate external events (queues, streams, topics) into Kubernetes metrics and let HPA handle the final scaling decision.

This hybrid approach reduces erratic behavior and improves stability.

2. Setting an Overly Aggressive Polling Interval

A pollingInterval that is too low can:

- increase load on external APIs (Kafka, Azure Service Bus, Prometheus),

- introduce latency and instability in scaling,

- generate unnecessary costs or throttling.

Best practice:

Start with conservative values (30–60 seconds) and reduce them only after observing real latency and throughput metrics.

Event-driven scaling should be timely, not hyper-reactive.

3. Not Defining maxReplicaCount

Leaving scaling without an upper bound is one of the most dangerous production mistakes:

- uncontrolled over-scaling,

- node and cluster saturation,

- unexpected costs.

Best practice:

Always setmaxReplicaCountbased on cluster capacity, event source limits, and maximum sustainable application load.

4. Hardcoding Secrets and Credentials in YAML

Embedding credentials directly in Kubernetes manifests:

- violates security best practices,

- exposes secrets in repositories,

- complicates credential rotation.

Best practice:

Use TriggerAuthentication with Kubernetes Secrets or external providers (Vault, Azure Key Vault, AWS Secrets Manager).

5. Ignoring Scale-Down Behavior

Many teams focus only on scale-up, but scale-down is often the most delicate phase:

- overly aggressive scale-down causes frequent cold starts,

- stateful or async cleanup workloads may lose in-flight tasks or messages.

Best practice:

ConfigurecooldownPeriodcarefully, test behavior with intermittent workloads, and ensure the application handles shutdown and retries idempotently.

Conclusion: When KEDA Really Makes the Difference

KEDA is a powerful but targeted tool.

It should not be used everywhere, but where workload is event-driven it delivers significant benefits.

Practical Takeaways

- Use KEDA when CPU ≠ work

- Always combine it with HPA

- Design scale-down before scale-up

- Treat secrets as first-class citizens

- Start simple, refine with advanced configuration

If Kubernetes is the operating system of the cloud, KEDA is what makes it responsive to the real world.