High Availability vs Fault Tolerance (and where Disaster Recovery fits in)

I often hear architects or clients confidently say:

“We have Fault Tolerance because we run two EC2 instances in an Auto Scaling Group with a Load Balancer in front.”

The reality? That’s not Fault Tolerance (FT) at all. It’s High Availability (HA)....and the difference is huge.

Why clarity matters

People working in infrastructure and cloud often use HA and FT as if they were synonyms.

They’re not.

And the difference is not just academic: it’s practical, real, and critical.

The words we use to describe a solution—whether to a client, a manager, or a colleague—shape how the value of that solution is perceived.

If you say you’ve built a fault tolerant system when in reality it’s only highly available, you risk two things:

- Creating false expectations. The client thinks they have an “uninterrupted” system, but during the first failover someone loses their session.

- Undervaluing your own work. A well-architected HA solution is already very valuable, but if you mislabel it, you come across as imprecise or naïve.

Words matter. In our field, calling things by their right name isn’t pedantry—it’s professional credibility.

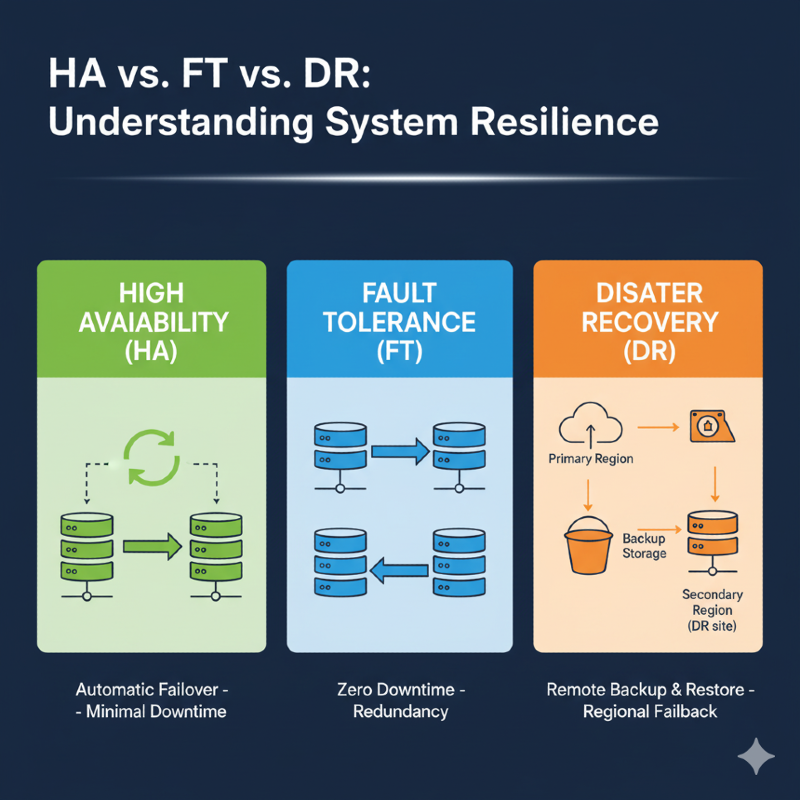

High Availability (HA)

Take the classic example: an Auto Scaling Group with two EC2 instances distributed across two Availability Zones.

That’s High Availability, not Fault Tolerance.

Why?

- In HA, if an instance dies, the ASG replaces it.

- The Load Balancer routes traffic to the healthy instances.

- But there’s always a perceivable failover:

- in-progress connections are lost,

- local sessions disappear,

- if the app isn’t stateless, you risk losing state or relaunching jobs.

This is pure HA: high uptime, short interruptions, but not invisible.

Concrete AWS examples:

- An Application Load Balancer with two EC2 instances in different AZs.

- Amazon RDS with a standby replica in Multi-AZ.

What happens during failover?

- The service “blips” for a few seconds.

- Some users need to refresh the page or log in again.

Formally, HA aims to maximize uptime by minimizing outage duration. It means accepting a few seconds of disruption, a re-login, or a job restart.

Fault Tolerance (FT)

Fault Tolerance is different.

FT’s goal is to keep operating with no perceivable interruption.

At most, you accept a degradation in capacity—but not an outage.

AWS examples:

- DynamoDB, which thanks to multi-AZ synchronous replication offers an experience very close to FT.

- Aurora multi-writer (where supported and workload-compatible).

- Active/active architectures with real-time state replication.

In these scenarios, during failover:

- The user notices nothing.

- Queries continue to return results.

- No session is lost.

In summary:

- HA = minimal downtime (seconds/minutes).

- FT = imperceptible downtime.

Disaster Recovery (DR)

Disaster Recovery comes into play when events exceed the limits of HA and FT:

- the loss of an entire region,

- a natural disaster,

- a major human error.

Here we’re not talking about seconds of failover, but strategies to restore service elsewhere.

Two key metrics: RTO and RPO

To discuss DR (and especially to choose between strategies), we need to introduce two key metrics:

- RTO (Recovery Time Objective): how long it takes to restore service after a disaster.

- RPO (Recovery Point Objective): how far back in time you may lose data, i.e. the maximum tolerable data loss.

Everyone wants very low RTO and RPO. The real question is: at what cost?

DR Strategies

In AWS, we can outline four main approaches, each balancing cost and RTO/RPO differently:

- Backup & Restore (Cold)

- Data stored in backups (e.g., Amazon S3 cross-region).

- In case of disaster, restored to new EC2/RDS instances.

- Cost: lowest.

- RTO/RPO: highest (hours or days).

- Pilot-Light

- In addition to backups, a minimal “core” is always active in a second region (small EC2/RDS).

- In a disaster, scale it up quickly.

- Cost: medium.

- RTO/RPO: medium (tens of minutes/hours).

- Warm-Standby

- A complete but scaled-down environment in a second region.

- In an emergency, simply scale it up to full capacity.

- Cost: medium/high.

- RTO/RPO: low (minutes).

- Multi-Region Active/Active (Hot)

- Multiple regions active in parallel.

- Route 53 handles failover or geo load-balancing.

- Cost: very high.

- RTO/RPO: ≈0.

Any DR approach requires orchestration (DNS, IaC, runbooks) and regular testing—without them, DR is just theory.

The metrics that matter

To get a sense of what the “nines” in availability mean:

- 99.0% → ~87.6 hours downtime/year

- 99.9% → ~8.76 hours

- 99.99% → ~52 minutes

- 99.999% → ~5 minutes

(These values are calculated annually; on a monthly basis they’re roughly one-twelfth of that.)

Moving from three to four nines isn’t just about adding another server:

It requires synchronous replication, active/active architectures, patching without downtime, 24/7 monitoring, and continuous testing.

All of this means more complex infrastructures and significantly higher operational costs.

How to tell them apart (and not get fooled by marketing)

A simplified way to look at it:

- If during failover someone needs to refresh the page → you’re in HA.

- If no one notices anything → you’re in FT.

- If an entire region fails → you need DR.

Don’t call something “fault tolerant” if it’s really just HA.

The truth is revealed in tests: turn off a node and see what happens.

Checklist with real examples

- High Availability (HA): ALB distributing traffic across multiple EC2s in different AZs, RDS Multi-AZ. Fast failover, but users may notice a refresh.

- Fault Tolerance (FT): DynamoDB with synchronous replication or Aurora multi-writer. No perceptible interruption.

- Disaster Recovery (DR): cross-region strategies like Backup & Restore, Pilot-Light, Warm-Standby, Multi-Region Active/Active.

In summary

- HA: high uptime, short but perceivable downtime.

- FT: continuous operations, imperceptible downtime.

- DR: last line of defense, with strategies based on RTO/RPO and budget.

Lessons from the field

Over the years I’ve worked on several enterprise projects:

- in the financial sector, where every second of downtime has massive impacts,

- and in more common contexts like e-commerce or corporate portals.

What I’ve learned is that in the vast majority of cases—nine times out of ten—well-designed High Availability plus a solid Disaster Recovery plan covers business needs more than adequately.

True Fault Tolerance, with RTO~=0 and RPO ~=0, is required only in scenarios where even a single lost transaction or session is unacceptable: for example, in high-frequency trading, life-critical medical systems, real-time industrial control, or other safety-critical environments.

In these cases, complexity and costs rise exponentially: you need architectures with synchronous replication, active/active multi-region deployments, and dedicated 24/7 SRE teams.

For all other workloads, the real challenge is finding the right balance between availability, cost, and operational simplicity.