When Cloud Becomes a Strategic Decision

For a long time, the cloud was a simple answer to a very concrete problem: speed.

Speed in releasing software, in scaling, in experimenting with new ideas without having to invest months in infrastructure planning.

Managed services played a decisive role in this transformation. Ready-to-use databases, reliable messaging systems, integrated identity, logging, and monitoring services. Infrastructure became invisible, and for many years this was a huge advantage.

The success of hyperscalers did not come from having “better” infrastructure in an absolute sense, but from offering a simpler experience. Fewer decisions to make, fewer possible mistakes, more focus on the product.

As often happens, the problem does not arise at the beginning. It arises when the cloud stops being a tactical accelerator and becomes a long-term structural choice.

When Simplicity Starts to Layer

After a few years, many organizations find themselves with platforms that seem to work perfectly, yet become increasingly difficult to change.

Not because technical alternatives are missing, but because the operating model has been implicitly absorbed by the provider’s ecosystem.

Databases, messaging systems, observability, identity: everything integrated, everything coherent, everything efficient.

And precisely for this reason, tightly coupled.

This is not a design mistake. It is the natural outcome of platforms built to optimize the experience within a single cloud.

At a certain point, however, the question is no longer “does it work well?”, but how much room for choice remains over time.

This is where the discussion stops being purely technical and becomes strategic.

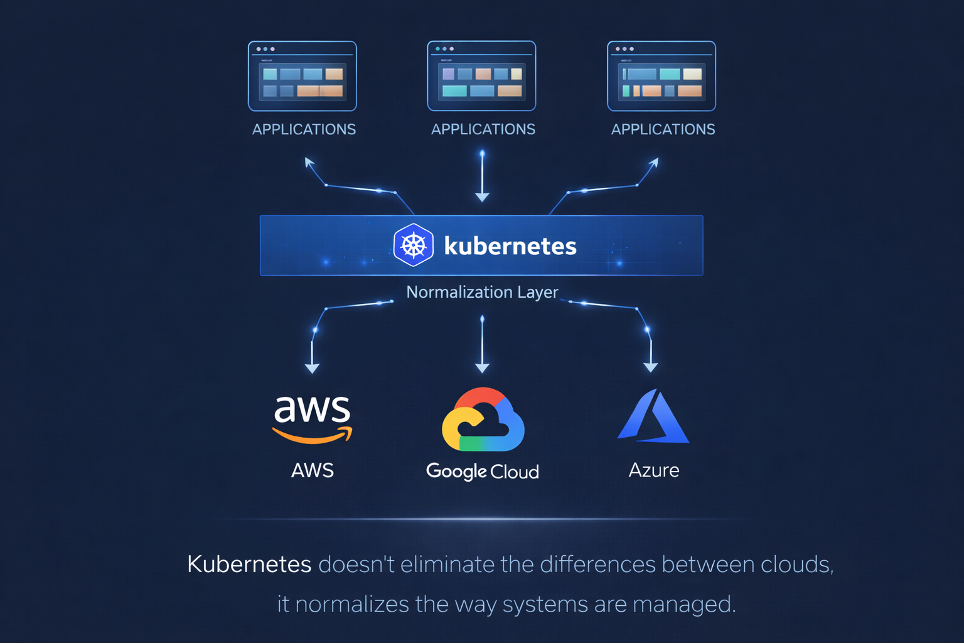

Kubernetes as a Normalization Layer

Kubernetes began to emerge in this space, often without much fanfare.

Not as an alternative to managed services, nor as a tool to “exit the cloud,” but as a normalization layer between applications and infrastructure.

Kubernetes does not eliminate differences between providers.

It eliminates the idea that those differences must necessarily dictate how a system is released, observed, upgraded, and governed.

In other words, it shifts the center of gravity from the provider to the operating model.

This is not a promise of abstract portability, but of consistency. And consistency, over time, is a powerful lever.

When Operations Become Software

The real discontinuity of cloud native is not in containers, but in operators.

With operators, a significant portion of operations—upgrades, backups, failover, scaling—stops living in documentation or individual expertise and becomes executable software.

This changes how value is distributed:

- infrastructure remains fundamental

- but operational intelligence is no longer tied to a single environment

When operations are codified, they can be versioned, tested, and transferred.

It is in this transition that the cloud slowly begins to resemble a commodity—not because it becomes trivial, but because it becomes replaceable given the same operating model.

A Platform on Kubernetes: Does It Really Make Sense?

At this point, a natural question arises:

does it make sense to build a platform where even traditionally “managed” services run on Kubernetes?

The honest answer is: it depends—but in many cases, yes, if the trade-offs are clearly understood.

A cloud-native platform on Kubernetes is not built to save money at all costs or to reject managed services. It is built to standardize how operations are carried out.

In this context, a typical stack might include:

- Postgres managed via CloudNativePG

- Kafka via Strimzi, when lifecycle control or multi-cluster consistency is required

- Keycloak for identity, when portability and governance are key requirements

- Observability based on OpenTelemetry, Prometheus, and Grafana, with Alloy as the collector

- Delivery and governance through Argo CD and GitOps

A Common Baseline, Pragmatic Choices

Cloud native as a maturity choice.

Kubernetes is not a mandatory destination, and cloud native is not a religion.

But ignoring the question they raise—who controls the operating model in the long term—is becoming increasingly difficult today.

The cloud won because it made infrastructure invisible.

Cloud native becomes relevant when it makes the decisions that matter visible.

And that is where it stops being a technical choice and finally becomes a strategic one.